Justice by Algorithm and Absurdity: Law, Trauma and the Windowless Courtroom

I Spent Years in Family Court. “The Dream Hotel” and “Mothers and Sons”—one speculative, one starkly realistic—show how 5-minute legal hearings can change lives

Original published on Medium in Book’s Are Our Superpower on June 11. Read more from the archives here.

After two decades in family courtrooms and too many falafel wraps on Chambers Street, I didn’t expect fiction to get it this right — or make me want to erase my digital footprint.

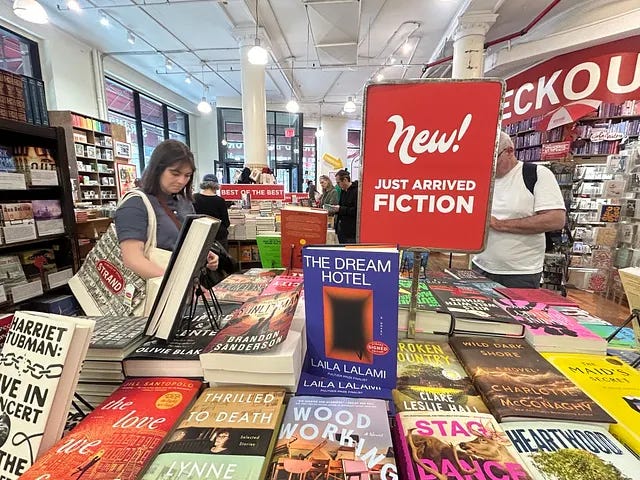

Laila Lalami’s The Dream Hotel and Adam Haslett’s Mothers and Sons aren’t courtroom dramas; they’re psychological indictments of a system that keeps you waiting, watching, and wondering if anyone is really in charge. One is speculative, the other painfully real, both of these novels understand how quick legal appearances change lives

Do not expect justice in a room without windows

That’s where both of these extraordinary novels have pivotal moments: in repurposed classrooms, converted conference spaces, and other bureaucratic dead zones where due process is an increasingly optional courtesy. If the flickering fluorescent lights don’t sap your hope, the procedural indifference will.

I’ve spent more hours than I can count in windowless courtrooms — family court, to be precise — where the only thing colder than the fluorescent lighting is the procedural churn. I’ve also eaten more falafels than I care to admit from food carts clustered around Manhattan courthouses, in between hearings that rarely start on time and often end in adjournments.

So when The Dream Hotel opens in a converted classroom and Mothers and Sons kicks off in yet another airless courtroom, I didn’t need to suspend disbelief.

The Dream Hotel by Laila Lalami (Pantheon, 336 pages) and Mothers and Sons by Adam Haslett (Little, Brown and Company, 336 pages) are Booker-worthy novels that explore the slow machinery of the American legal system. Lalami leans into speculative fiction with psychological precision, while Haslett brings literary interiority and dark humor to legal realism. One operates in the near-future; the other in our all-too-broken present.

Powerful and precisely imagined, Lalami’s novel unfolds in a near-future dystopia where corporate surveillance and government control converge — and dreams become data. When Sara Husien lands at LAX after a conference in London, agents from the Risk Assessment Administration (RAA) detain her. Their algorithm has flagged her as a threat to her husband, based on dream data. She’s sent to a privatized detention center — not for anything she’s done, but for her dreams. She’s detained at LAX and transported to a corporate holding center called Safe-X, an eerie, rule-bound facility where women like her are held for crimes they haven’t yet committed. As the rules shift and her stay extends, Sara finds herself increasingly trapped in a nightmarish system with no clear way out.

Here’s the true horror: Sara chose to implant the DreamCatcher.

She opted in — just like we all do cookies, scroll when we agree to endlessly through streaming platforms, and hand over our lives to tech platforms in exchange for convenience. The parallels aren’t subtle. (I spent half the book wondering if I should delete my Apple Health data. For starters.) Her dreams become corporate data, analyzed for evidence of deviance. One algorithm labels her a potential threat. That’s all it takes.

I spent the book wondering if I should delete my Apple Health data. For starters.

Her first hearing comes with only 24 hours’ notice. The venue? A prekindergarten classroom, where coat hooks still hang at a child-height. Her lawyer arrives late, without notes. One violation she’s accused of never happened. Her lawyer stays silent. He scrolls through his phone — searching for her file, she hopes, but who knows? — and says nothing. “Aren’t you going to say something?” she finally asks. He doesn’t. She isn’t released.

Things spiral. One “proceeding” isn’t a hearing at all, but an “expedited assessment” held in a music room. She is told it will be more efficient. Which, if you’ve ever sat through a vendor-led software training labeled “Efficiency Initiative,” you know is never a good sign.

But the longer Sara remains in the system, the more apparent it becomes that no one intends to help her out of it. Lalami’s genius lies in how little she exaggerates — the dystopia is a few bad headlines away from our current reality. CECOT prison in El Salvador springs to mind

If The Dream Hotel is an allegory of algorithmic control, Mothers and Sons is a boots-on-the-floor immersion in the trenches of immigration law. Adam Haslett, also a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in Fiction, gives us Peter, a weary New York asylum attorney who spends his days fighting the good fight.

“The courtroom is windowless. They all are,” the novel begins.

Fluorescent lights glare. Respondents are huddled with lawyers on benches, waiting their turn in a process where it must seem to them turn on “technicalities” — i.e., legal procedure — matter more than truth. Did the petitioner get the right notice? Is their country of origin “designated” properly? Is it even the right time to discuss hardship?

It reads like a dark procedural farce — if the stakes weren’t so dire and so realistic. One lawyer refuses to name a country for his client’s removal, why make the government’s job easier? The judge assigns one anyway. He then, briefly, invokes the Convention Against Torture. The Homeland Security lawyer points out he asylum seeker has a theft conviction, so his removal is expedited.

Next up? Calendaring — finding a time when the judge, two lawyers, and a Russian translator can all squeeze into the same room. The judge consults a “wrinkled dot-matrix printer page,” the lawyers scroll through their phones like they’re booking a dinner reservation.

Few judges asks the asylum seeker if Thursday at 9:15 three months from now works.

(Instead, their lawyer leans over, whispers, and their client nods — because it’s easier than explaining they have no idea what their child-care-work-schedule situation will be.)

After they receiving a continuation they requested — because the client is still collecting documents to support asylum application — Peter stresses they must need to show up on time. His job is calandering and client wrangling.

The realism extends to the small, frustrating moments of everyday life. Peter goes to eat at “Pret,” i.e. Pret A Manger, and the line is out the door, so he settles for a coffee and falafel from the food cart on Chambers Street, and eats his wrap while listening to his voice mail on the №1 train. Been there. Different courthouse, same falafel.

Readers should know the book isn’t all focused on the asylum lawyer’s work. (Although that would be just fine with me, the more hearings the better.) There is a whole plot with the lawyer’s mother — a minister who comes out later in life and starts a retreat in New England. There are a lot of group therapy sessions. Intertwined with his legal work is his emotional disintegration: a deep, unresolved trauma tied to his mother. His obsession with a vulnerable gay Albanian client — whose asylum case becomes a mirror for Peter’s own haunted identity — gives the novel its heart and deepest stakes.

Both novels balance procedural realism with literary muscle. Both have a dry, gallows humor. And yet — sometimes the system delivers. Late in Mothers and Sons, Peter sits in a park across from a federal courthouse — reflecting that it is the rare place where something real might happen. As Haslett writes: “A legal standard gets tweaked; a rule of timing is modified; the precise quantity or quality of what one subject of asylum seekers must show to remain out of danger is slightly adjusted.”

These books aren’t hopeful, but they aren’t entirely hopeless either. In their dark humor, psychological acuity, and precision of language, they remind us of what’s at stake if systems are left to run on autopilot — and what can still happen when someone fights back. In systems built to forget people, literature like this keeps the record.

Boilerplate

As always, Judicial Junkie doesn’t aim to provide comprehensive book reviews. The lens here is legal, procedural, and highly subjective — focused on what grabs my interest, including food carts in lower Manhattan.